Auteur : Agence Science Presse - Catherine Couturier

The noisy minority falsely claims that “COVID-19 is no worse than the flu”. The majority is worried about the pandemic’s final scale. But there’s one point of agreement. It’s very difficult to determine the exact percentage of deaths caused by this disease. This has helped sustain public confusion. The Rumour Detector explains why it’s so difficult to separate fact from fiction.

To simplify, scientists sometimes talk about the mortality rate. This term refers to another concept used in demography. It means the number of deaths relative to the total population, for a given period. In Québec, for example, the mortality rate, all causes combined, was 8 people per 1000 in 2019. You can also talk about the mortality rate linked to car accidents, heart attacks, etc.

But when measuring the number of people who die relative to those who caught a disease, the term “fatality rate” is used instead.

1. Hard to account for cases

At the start of the pandemic, this seemed fairly easy: just divide the number of victims by the number of people infected.

That’s what the World Health Organization (WHO) did on March 3 at a media briefing. “Globally, about 3.4% of reported COVID-19 cases have died.”

This figure startled many specialists. Because this figure in fact was based on the number of deaths relative to the number of cases known and confirmed at that time. “Known and confirmed” meant that the WHO didn’t count people who had been contaminated but didn’t know it. This was either because they couldn’t be tested, or because they didn’t have symptoms.

Remember that in Québec, at the start of the pandemic, only travellers or their close relations were being tested. After that, it was mainly healthcare workers.

This rate evolved over time, as different countries increased their screening capacity.

Also, countries don’t calculate cases the same way. Each country’s strategies have evolved over time. Some only consider cases that tested positive in the lab (like France or China at the start of the pandemic). Others add clinically confirmed cases (based on the symptoms or a lung X-ray). Still others include cases confirmed by an epidemiological link. For example, if someone tested positive and other members of the household got sick, all of them would be considered to have caught the virus. Québec even changed its strategy in March to add probable cases to confirmed cases in the total.

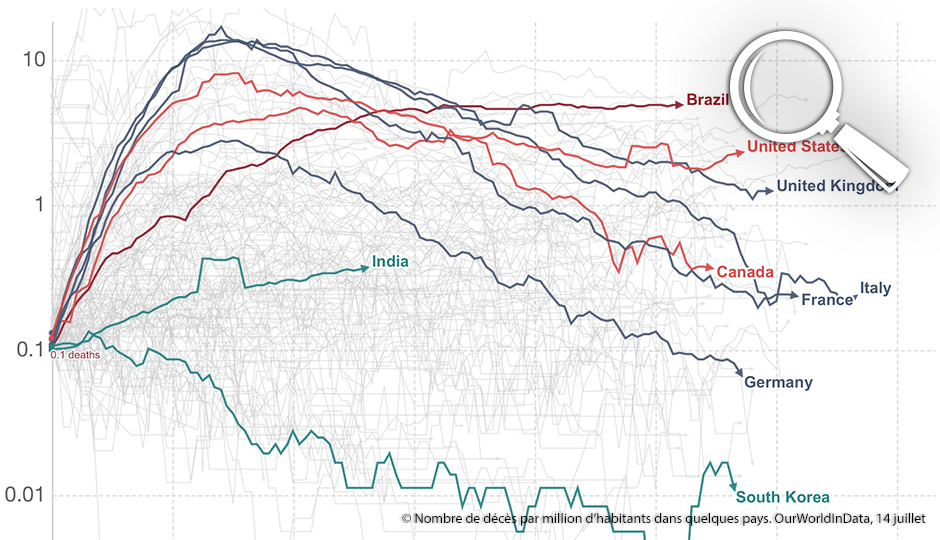

That’s the main reason why the fatality rates vary greatly between countries, and even between regions. But other factors exist: a population with a higher average age, a poorer population, or the absence of a health insurance plan…

Researchers are now working to establish the infection fatality rate, or IFR. This number is harder to obtain, because it includes these “invisible” patients and their proportion is still unknown. A popular science article in Nature recently explained that the COVID-19 IFR was particularly tricky to calculate.

That’s because a large number of people who are symptomatic or have mild symptoms pass under the radar. It will take several months, until the end of the pandemic, for everyone to agree on a calculation.

2. Hard to account for deaths

Here’s another difficulty. Countries, (or even regions, as in the United States) don’t calculate all COVID-related deaths the same way. In some places, (like Italy, Sweden or England), the numbers exclude people who died anywhere but the hospital. Deaths without confirmed lab results are also excluded. Establishing the cause of death may take several days, creating delays in the official data.

3. Waiting for the dust to settle

Several studies now point to a fatality rate of 0.5% to 1% (and currently seem to be converging on 0.6%). That means that out of 1,000 people who have COVID, 5 to 10 will die. The rate may be higher for some age groups. Or it may vary depending on socioeconomic conditions, health or access to care.

In comparison, the fatality rate of the Spanish influenza was 2.5%. The fatality rate of the seasonal flu is traditionally estimated at 0.1%. But the real percentage could be lower. That’s because many people suffering from flu were never hospitalized or tested, as in the case of the coronavirus.

We’ll have to wait for the dust to settle, at the end of the pandemic, to know the real fatality rate. That’s when the figures will be compiled and validated. A quick look at the excess deaths (the number of deaths for comparable periods) gives a good idea of the pandemic’s effects. The first months of 2020 are compared with the first months of the previous years.